The Phenomenology of Nyarlathotep

An anti-philosophical “philosophical” investigation of Wonderful Everyday (Subarashiki Hibi/Subahibi) as well as Tsui no Sora.

Obviously, this post will spoil Subahibi and Tsui no Sora (both the 1999 version and the Remake).

You can also read this post in:

A major difficulty with the 2010 visual novel Wonderful Everyday: ~Discontinuous Existence~ (AKA Subarashiki Hibi ~Furenzoku Sonzai~, or, Subahibi) is that, despite being first and foremost a work of art that demands the usual habits of a good art critic—emotional honesty and aesthetic openness—it also goes out of its way to invite the distant and abstract pose of a philosopher. This is a game where characters quote and discuss famous philosophers at length. Its most famous catchphrase and thematic heart—the exaltation to “live happily"—is a riff on an excerpt from Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the most striking and bold philosophers of the 20th century. This means that exercises in bare literary or artistic analysis of Subahibi, no matter how excellently done, tend to appear somewhat less expansive and wide-reaching than the material that they purport to analyse.

On account of this challenge, I have only ever felt like it was proper to take little bites out of Subahibi—to snack on its ideas, like they are small pieces of liqueur chocolate. Doing anything further presented a task that had a certain unboundedness to it that is not conducive to how I ordinarily wish to write about art. In the case of discrete media analysis—even with works that present very complex or expansive themes, and even in those cases on this blog where we have gone above and beyond with comically large posts—it is quite possible for the critic to limit themselves to a particular lens or element of the work. But what follows will not be such a self-contained literary analysis of Subahibi. This will not be a review of Subahibi’s place within a bounded artistic framework or lens. It will be an open-ended response to the concepts and worldview that comes across in the whole of that fictional work.

Unfortunately, this approach will also have the side-effect of sterilising Subahibi’s uniquely artistic value. The power of art is exactly that it can exist in a state of flux and indeterminacy which is inaccessible to a philosophical treatise. Even when an essay lands on a conclusion that rejects certainty or embraces ambiguity, it still unavoidably stakes out a position on the validity of certainty itself. Set next to the cold and inert pursuit of truth, the artist retains an enviable luxury: the artist can get inside the experience of thinking beyond understanding, and bring its essential truth as an experience to light. Subahibi definitely “says things” about reality, and we will centre these claims in our own approach to the text. However, in doing so, we will lose our connection to the opacity and liquidity of human experiences that can only come through in a work of art. This chiefly means that when we transform Subahibi into a specific worldview to be examined philosophically, we will be locking in place something that is better understood in its fluidity. There will be occasions when we lay out certain “claims” as being “made” or “argued for” by the game, and some readers may find it less than obvious that Subahibi presents anything so conclusive as these resultant positions. They might find the picture of the work that appears below to be overly simplified and reductive. I can only say that I tried my best to minimise this problem while recognising that it is an inevitable feature of the subject matter and methodology of the post, as well as my own flaws as a writer.

The ground of our discussion will be far more fundamental and structurally expansive than even the already fairly pedantic and long-winded output typical of this blog. We will have to let this text—everything in it, whether diegetic or didactic—congeal into a unitary whole that we can, in turn, confront with our own arguments about the nature of the world on a similar scale. This necessarily unbounded methodology presents clear challenges. For one, this post will be dense and hard to read—more so than normal. For another, it has ballooned out to such a scale that I worry as to whether I have succeeded in threading it all together. Nonetheless, I believe the end result remains worthwhile even in light of these limitations.

The structure of the argument will proceed as follows:

In Part One, we will draw out the philosophy of Subahibi as it is presented by the game and by its historical context.

In Part Two, we will dive into a slice of political theory on cult dynamics and terrorism as an added interpretative context for the events depicted in Subahibi’s plot.

In Part Three, we will answer the solipsistic tendencies in Subahibi with our own attempt at an onto-political argument for phenomenological materialism.

Unfortunately, my attempt to directly respond to Subahibi will only properly arrive after the above groundwork has been completed. But for the moment, I would like to offer a primer on the overall point that this essay will gesture towards. And this will come by way of an explanation of its subtitle: This essay, like Subahibi itself, will centre on a number of “philosophical” concepts. We will step beyond the authors directly cited in the game itself and consider a wide range of thinkers from across the world. However, at the end of this sojourn, our overall standpoint will amount to an argument against philosophy as the proper frame in which to situate the themes and motifs that appear in Subahibi. We will suggest that Subahibi is limited by the conditions that push it to look inwards towards the philosophical mode of contemplation as the means to “live happily” in a contemporary capitalist society. Life, whether lived happily or not, is not located in the brain. Life is lived in our physical world which we share with others. And the crisis of our times is, correspondingly, a crisis of political action in the world, not philosophical thought in the brain.

Part One – The Void Beyond the Brain

Wonderful Everyday: ~Discontinuous Existence~, or as it is often known, Subahibi, is a Japanese denpa horror visual novel developed by KeroQ and released in 2010. It features a scenario primarily written by Sca-Di (SCA-自), with assistance from Ayane, Chitose, and Kenichi Fujikura. Technically speaking, Subahibi is a kind of remake or reimagining rather than an original story. Its core plot closely follows the events of Tsui no Sora—a visual novel from a decade prior (1999), also made by KeroQ and Sca-Di. And as with Tsui no Sora, Subahibi’s structure is a kind of anthology narrative, where the breaks in continuity offered by each chapter rely on a shift in narrator and perspective, rather than depicting entirely different events in the narrative. Tsui no Sora in particular can be described as a game that tells the same story several times over from multiple points of view. Subahibi has a few exceptions to this formula, but it maintains an essential interest in the problem of exploring multiple perspectives on a single event.

The centrepiece of the action in both games is a spontaneous doomsday cult that forms in response to the suicide of a student named Zakuro Takashima. The cult takes up residence within an unused underground section of Kita High School, and is led by a teenaged boy named Takuji Mamiya. This impromptu organisation is oriented around a prophecy that the world will end on the 20th of July (in 1999 and 2012 respectively, depending on the game), and which quickly balloons in size during the week leading up to the apocalyptic date in question. While each of the games utilise this scenario to develop overlapping stories centred on similar horror elements, there are also significant differences in their approaches to this same overall motif.

One particularly illustrative example of these variations can be found in the character of Tomosane Mamiya. Tomosane appears to suffer from a dissociative condition such that several characters who are discrete, separate people in Tsui no Sora (Takuji Mamiya, Yukito Minakami, Kotomi Wakatsuki) only strictly exist in Subahibi through Tomosane’s perspective. He himself also occupies multiple identities and perspectives throughout, with the Chapters for Yuki Minakami, Takuji Mamiya, and Tomosane Yūki taking place “within” the same physical body of “Tomosane Mamiya.” In this sense, Subahibi transforms Tsui no Sora’s “[telling] the same story several times over from multiple points of view” into “telling the same story several times over from the ‘same’ point of view with the appearance of multiple points of view.” This allows the game to use the expectations set by its format to develop an implicit commentary on identity, subjectivity, and perspective.

Structurally speaking, Subahibi is made up of seven main segments: (1) Down the Rabbit Hole I, (2) Down the Rabbit Hole II, (3) It's my Own Invention, (4) Looking-glass Insects, (5) Jabberwocky I, (6) Which Dreamed It, and (7) Jabberwocky II. There are five total narrators, with each respectively corresponding to one of these chapter titles (repeat titles have repeat narrators). There is, however, a more conceptual way of organising these chapters.

Subahibi has two overriding storylines: Firstly, there is the sequence of events that result in Takuji Mamiya’s cult. Secondly, there are the mysteries that culminate in the revealed identity of Tomosane Mamiya. Launching off from this segmentation, we can break the chapters up into one group that primarily deals with the cult plot, and into a second group that primarily deals with the Tomosane plot. Chapters one through three belong to the former group. Chapters five through seven belong to the latter group. Chapter four lies in an intermediate position, where it begins to address the revelations of the Tomosane plot whilst keeping a fundamental thematic connection to the cult plot. Setting off on our inquiry into Subahibi will necessitate a pair of sequential analyses of the themes contained in each of these two divisions. However, Subahibi does not end after chapter seven. It also features an epilogue chapter titled Tsui no Sora II and a bonus chapter called Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door. Of these two, the epilogue chapter is of significant importance for our analysis. We will therefore append it as a third topic for our consideration.

First division: Everyday nihilism as cosmic horror

On the 20th of March, 1995, fourteen people were killed and thousands more were seriously injured when the Japanese doomsday cult, Aum Shinrikyō, attacked the Tokyo subway line using sarin gas—a military-grade nerve agent. This came just two months after approximately five-thousand people were killed in the Great Hanshin earthquake—Japan’s second-most lethal earthquake of the 20th century. The middle of the 1990s also saw the entrenchment of the “Lost Decades” of economic stagnation and the “freeter” (underemployment) crisis.

Later, in February 1997, the 14-year-old boy Shinichiro Azuma assaulted two younger children in the Kobe area. His crimes quickly escalated from there as he continued attacking children throughout the first half of 1997. In March 1997, he even bludgeoned a 10-year-old girl to death. And most dramatically, in May 1997, he strangled an 11-year-old boy, beheaded him, and displayed his head at a local elementary school to taunt the public. Once he was caught, the young age of the culprit and his nihilistic (lack of) motives naturally led to frenzied media coverage.

It is impossible to properly situate Tsui no Sora’s poignant sense of apocalypticism and dread without reference to the atmosphere of sheer cosmic misfortune that dominated Japan in the era leading up to its release. To say that Tsui no Sora is “based on” the Aum incident understates the case. Tsui no Sora bathes in the zeitgeist of the late 1990s and its rapid succession of extreme incidents. It marinates in the palpable sense of hopelessness and directionlessness of a youth culture where the oncoming end of the millennium felt equivalent to the end of all meaning. It depicts a time when the sights and sounds of ordinary Japanese city life took on the same feeling as Gustaf Johansen uncovering the nightmarish city of R'lyeh. Subahibi, for its part, as a kind of reimagining of this same story, must be understood in its relationship to—even in the sense of explicit distance from—this historical zeitgeist.

In the immediate wake of the Aum incident, the sociologist Shinji Miyadai quickly published the 1995 book, Living an Endless Everyday Existence: A Comprehensive Guide to Overcoming Aum. On account of its easy readability and fairly original thesis, the book had a lasting influence on interpretations of the Aum incident. Miyadai rejects the popular theories that explained Aum’s violence via the decline of traditional morality or via new “anti-reality” cultural trends such as anime and otaku culture. Instead, he suggests that cults like Aum are a misallocation of people’s capacity for ethical conscientiousness. Such ethical awareness leads to utopian aspirations for an absolute form of goodness, but these desires are misplaced in a secular age that cannot live up to the pre-modern ideal of absolute cosmic justice.

For Miyadai, humans naturally desire transcendence or an “outside” beyond themselves that they can act upon and through. However, the progress of humanity has gradually produced an inescapable “inside” realm made up of technologically mediated, subjectivised states of existence. Notably, Miyadai argues that this progress is itself a good thing. He also highlights the empirical reality that social and technological progress has continued throughout much of human history, and that it cannot be simply frozen or reversed indefinitely. The problem lies in the fact that, even if progress is both desirable and inevitable, it nonetheless produces a dangerous kind of ontological isolation that frustrates the natural desire for transcendent action. Utopianism and cult-like extremism are each symptomatic of this frustration. Therefore, Miyadai calls for the negation of these symptoms through a political embrace of an “endless everyday existence,” rooted in the simple and relativised happiness of daily life in a stable capitalist society.

Tsui no Sora is responsive to this mindset in several interesting ways. The starting narrator of Tsui no Sora is Yukito Minakami. And one of Yukito’s most significant flaws in the story is that his common sensical attachment to the logic of everyday existence blinds him to the danger posed by Takuji and his cult. Because Yukito is so steadfastly committed to the seemingly obvious fact that the world will not end on the 20th of July, he fails to appreciate the contagiousness of the nihilism and apocalypticism that spreads throughout the school after Zakuro’s death. The end result of this miscalculation is that Yukito is unable to respond when his friend and love interest, Kotomi Wakatsuki, is kidnapped, tortured, and raped by the cult. It is fair to say that Yukito’s experiences in the story form an implicit criticism of the naïveté contained in the endless everyday existence mindset: Yukito is the most conventionally thoughtful and “correct” character in Tsui no Sora, but these attributes are rendered useless, or even harmful, given the frenzied social collapse around him.

Subahibi has its own analogue to Tsui no Sora’s first chapter, but it appears in the game’s second chapter, not its first. Subahibi’s second chapter has the same surface appearance as Tsui no Sora chapter one, with minor variations in the cast (Yuki Minakami as the female version of Yukito, for example). However, its thematic meaning is also shifted subtly. The presence of Subahibi’s own first chapter is a key culprit behind this difference. In Subahibi chapter one, Down the Rabbit Hole I, Yuki experiences a lighthearted, romantic school life in a world where Zakuro never commits suicide and where the Takuji cult never appears. Yet, this ideal world gradually unravels and comes to seem more like an elaborate intertextual structure—built up of allusions to Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand, The Brain is wider than the Sky by Emily Dickinson, Night on the Galactic Railroad by Kenji Miyazawa, and Through the Looking-Glass (as well as other related stories and poems) by Lewis Carroll—rather than anything concrete or real.

There are a range of viable plot interpretations that one can bring to the first chapter of Subahibi—especially in light of its playful attitude towards the concept of reality. But at least on a thematic level, the chapter’s most visible effect is to present an endless everyday existence, which we can interpret in the Miyadai mode. It thereby serves as an absolute contrast to the extraordinary events that occur in the subsequent second and third chapters. However, where Yukito’s obliviousness and rootedness in everyday life was a clear personal shortcoming in Tsui no Sora, Subahibi begins its divergence from the prior text by taking a more equivocal stance on the danger of everyday happiness. The game’s overriding motto—to “live happily”—affirms such a lifestyle more than it condemns it. Yuki’s lesbian romance paradise (chapter one) admits upfront that it is unlikely to be real in a conventional sense. But as the game unfolds, it also becomes clear that this unreality is less of a problem than it might originally seem.

In the world of the first chapter, “there is one singular girl. No, there is a girl who is the world itself.” And that girl must find and return to her beginning and her end in the sky. Moreover: “The Brain — is wider than the Sky — For — put them side by side — The one the other will contain With ease — and You — beside.” Where can one find this sky with the girl who is the world? On the roof. And “by roof, you mean a place where you can see the sky.” On such a roof, Ayana Otonashi “came to see.” But “see what? The sky?” Not exactly, “the entire world. […] What do you think of the scenery you can see from this rooftop? […] You can see the city. Because this is the rooftop, you can see the sky, and you can see the city. […] You can’t see the city that lies beyond that, or what lies even further beyond that still. […] What if you could know what lies beyond the scenery you see, and beyond that still, and still further beyond that? The endless succession of beyonds.”

Unfortunately, we cannot simply translate a specialised vocabulary like this into a commonplace form of meaning that could tell us what is happening canonically in Subahibi chapter one. But we can at least add our interpretation to the chapter within the boundaries of its own vocabulary. The endless everyday existence of Subahibi’s first chapter is enclosed within the inside of the sky. And by that, we mean something that fits within the brain: “For — put them side by side — The one the other will contain With ease — and You — beside.” The world is a singular girl, and therefore the question is not so much what is happening in the chapter, but where and who. This endless everyday existence is not falsifiable in the manner of a what. It is the horizon of a sky, and centres on the search for the beginning and end of that same sky. Ayana, by contrast and for her part, is looking at the transcendent—at the outside beyond that sky, at the End Sky. Her question is whether the End Sky is even a beyond at all, or whether it instead fits within the brain like any sky.

This is all to say that Subahibi uses its commentary on the concept of reality to make a partial break with Tsui no Sora’s criticism of Yuki(to) for remaining within an endless everyday existence. In and of itself, an endless everyday existence is not any more or any less oblivious to the “realities” of its surrounding zeitgeist. It simply corresponds to one possible standpoint from which to view the sky. But the implied equivalency of such standpoints is precisely why chapter one’s positive interpretation of an endless everyday existence must be inverted by the very next chapter. Subahibi chapter two revisits Tsui no Sora’s critique of the endless everyday. Yuki undergoes the same traumatic failure to prevent the kidnapping and grotesque abuse of her friend and potential lover—in this case, named Kagami Wakatsuki. However, it is also at this juncture that the chapter offers another confrontation with the problem of unreality. Inconsistencies and impossibilities pile up in the story that we are experiencing through Yuki’s perspective until, finally, Kagami’s definite presence disintegrates and a stuffed animal appears in her place.

With the benefit of later chapters, we can point out that the crime in question did not exactly occur in a literal—or at least in an objective—sense. “Kagami” was only ever a stuffed animal in the possession of Tomosane Mamiya’s younger sister, Hasaki Mamiya. Moreover, the instigator behind the “torture” of “Kagami” was Takuji—an alternate identity who shares Tomosane’s body along with Yuki in the first place. The punishment that Yuki suffers for failing to face up to the cult is clouded over by the same kind of opaque sense of unreality that infused Yuki’s comparatively successful endless everyday existence in the first chapter. Put another way, the problem of reality supersedes the distinction between the everyday and the extraordinary. In Subahibi, the cult no longer corresponds to the reigning truth of the historical moment, whereas the cult in Tsui no Sora was given a privileged viewpoint by the crisis of the 1990s. This indeterminacy is made exceedingly clear once we view the cult from the inside during chapter three of Subahibi.

The third chapter of Subahibi takes up Takuji’s perspective. Where chapter two was centred on how to face up to the cult phenomenon from its outside, this third chapter concerns itself with the sociological and psychological formation of the cult from its inside. Takuji is a deeply isolated and weak person, as well as the victim of severe bullying. He is an archetypal otaku in his heavy dependence on fiction. And he also spends much of his time totally absorbed in a range of power and sex fantasies. Takuji’s sense of victimisation and his extreme inwardness can be read together by their shared connection to ontological isolation—that is, to the condition that Miyadai identifies with the subjectivity of our technologically mediated society. It is not just that Takuji happens to suffer pain or misfortune in a generic way. He suffers from a specific form of world alienation, rooted in the sensation that his suffering originates in the cold and foreign world of “common sense.” The technologically mediated world of mass society proceeds autonomously without his input, and Takuji therefore feels as though others only exist beyond the border of a fully inaccessible outside.

At least on a psychological level, the immediate catalyst behind Takuji’s attempt to establish a cult is the one-two punch of, firstly, his impression of a romantic connection with Zakuro (this is not entirely untrue, but it is still rooted in a misunderstanding), followed by, secondly, her death. By their nature, love and reproduction are structurally infused with the meaning of ontological transcendence. Takuji perceives Zakuro as the only vessel that would allow him to escape—eject, shoot, ejaculate—out of himself. (This is of course libidinal and gendered—but that topic is better left to other essays about other stories.) To take an overly pseudo-psychoanalytic framing, Takuji’s desire to reproduce boomerangs back to him in the form of a grotesque encounter with death and mortality. This scares him shitless and he retreats into the depths of his “secret base” in an unused underground section of Kita High School. There in the darkness, he, as Ayana puts it, comes into contact with Nyarlathotep—the Crawling Chaos. But at least in Takuji’s mind, this is actually an encounter with the “Magical Girl Riruru-chan,” who helps him to transcend his prior existence and become the “Saviour.”

Takuji is the one and only Saviour, but the majority of other cult members go through a comparable journey. Even prior to Zakuro’s death, many of the students of Kita High School were presented as being dissatisfied with their endless everyday existence. They were drenched in anxiety—that is, as Heidegger defines it, fear with no object or directionless fear. But after Zakuro’s death, this anxiety acquires a definite object in the idea that their endless everyday existence could transform into a sudden and meaningless death. Their anxiety therefore actualises into a concrete sense of terror. Such terror explodes out in the utopian desire for transcendence that is identified by Miyadai. Takuji’s prophecies easily play on this desire since they are explicitly structured in terms of “escape” from the corrupted “false world” and entry into a perfect “real world.”

For her part, Zakuro’s own chapter happens to feature a total divergence in its events based on the choices of the player. Even when the game features choices in the other chapters, the variations are usually either superficial or are limited to just the conclusion of the narrative. The comparatively darker route within Zakuro’s chapter is closely connected with the cult plot, whereas the happier route is most related to the Tomosane Mamiya narrative. This is intuitive enough, since the darker route follows the general skeleton of the Zakuro chapter in Tsui no Sora. In sticking with typical visual novel conventions, we will hereafter call Zakuro’s darker route the “true end,” since it is canonical to the other chapters. The alternative will instead be the “good end.”

The Zakuro true end is a kind of thematic antecedent to Takuji’s cult—and this is, in all likelihood, why the Zakuro chapter originally preceded the Takuji chapter in Tsui no Sora. Zakuro, like Takuji, is an insulated and victimised person who often retreats into fictional contexts as a survival mechanism. This parallelism is not just a matter of connecting these two individuals specifically, even if their intersection is a key feature of the story. It is also that Subahibi depicts a kind of world alienation as the default mode of existence in contemporary Japanese capitalism. Only exceptionally headstrong personalities such as Yuki are able to successfully navigate this alienation and apocalypticism to any appreciable degree. Relatedly, one of the primary points of differentiation between Zakuro’s story and Takuji’s lies in the fact that Zakuro encounters and then falls in love with Yuki—who, misleadingly, exists in the guise of Takuji via the body of Tomosane. Or to put things in a more conceptual light, we might say that Zakuro’s point of difference lies in her capacity to sincerely fall in love, in a manner that is not true of the cynical and narcissistic Takuji.

Zakuro seeks an escape from her endless everyday existence, but she also has a fundamentally outer-directed desire to incorporate others into this escape. Insomuch as she wants to reach a transcendent new world, she longs for a world that she can share with others—especially with Yuki, in the manner that we see in Down the Rabbit Hole I. In and of itself, the problem of love and otherness, within the horizons of the extreme subjectivity inculcated by an alienated endless everyday existence, is an exceptionally important motif during the first four chapters of Subahibi.

Yuki’s rootedness and steady temperament gives her an unusual capacity for facing up to the challenges involved in living an endless everyday existence. However, the flipside of her resistance to the alienating structure of contemporary life is a certain blindness—or even outright stupidity—when it comes to others and their own dislocation from the world. Takuji exemplifies such dislocation, being so extreme in his subjectivity and alienation that even the dramatic acts of transcendence and unity undertaken within the context of his cult are at most fleeting and superficial experiences for him. Zakuro here offers a curious intermediating point between these positions, since whether or not she continues to live an endless everyday existence depends on decisions that are left to the player: if she faces enough suffering and horror, she can succumb to alienation and nihilism, leading to the true end where she reaches for transcendence through death.

The sheer contingency that this structure introduces into Zakuro’s story is a significant point of departure between Tsui no Sora and Subahibi. In Tsui no Sora, Zakuro begins at rock bottom: She is suicidal from the outset and the narrative simply tracks her unerring journey from depression to an apocalyptic death fantasy. As for Subahibi, Zakuro’s newly indeterminate fate shines a light on certain nuances that appear within the text’s reinterpretation of nihilism. While it agrees with Tsui no Sora that ontological isolation and alienation are the default condition of an endless everyday existence in contemporary Japan, it takes much greater care to draw attention to how the most horrific forms of alienation—those that bring about the hellish desire for absolute transcendence and death—flow from concrete sources of misery and cruelty, as opposed to Tsui no Sora’s ambiguous, generalised atmosphere of doom.

Second division: The mind–body problem is wider than the sky

A cornerstone image that sustains the rest of Subahibi can be found in the famous graphic of Yuki standing atop a skyscraper in the middle of Tokyo—her eyes absorbed by the awe-inspiring, wide open azure sky above her, as she smokes a cigarette and thinks over the meaning of existence. This moment also features a more figurative undercurrent: it expresses something like the unity between an isolated individual thinker and the boundless world of the sky. Beyond anything else that we might try to say about the game, this metaphor cuts straight to the beating heart of Subahibi as both an aesthetic and a philosophical experience.

Subahibi places a lot of weight on the idea of the sky. Within the philosophical vocabulary of the story, the sky is a stand in for the enclosed infinity of the world itself. This is spelled out during the climax of Jabberwocky II, when Yuki and Tomosane stare at the universe and think over how the endless expanse of a starry night can be captured within the limited horizon of their individual brains. But even prior to this, a considerable amount of time is spent throughout the story on various rooftops contemplating the different skies that characters see. Some people see the same kind of limitless blue sky as Yuki; they are taken in by the boundless potential of a world whose only limit is the beholder themselves. Others instead see the End Sky—a sky that heralds a life lived within the boundaries of a determined end point, such as the 20th of July, 2012.

The young Tomosane and Yuki of Jabberwocky II are not actually the first characters in the story to grasp the endlessness of the sky in this manner. Earlier in that same chapter, Hasaki has her own memorable and poignant encounter with the sky. After the death of her father, she wanders to the same hill where the climax of the story is to later take place. The sky she sees from there is roughly the same kind that Tomosane and Yuki witness later, and she therefore draws a related conclusion: The unending infinity that Hasaki finds in the starry sky stands in sharp distinction to the boxed-in world of certainty which she had been promised by the adults around her. She had been told that her father’s death meant that he was waiting in the stars—that death lies in the sky. She instead learns that those stars are impossibly far away from human life. In essence, she learns that human life is the limit of the world, and that humans can never reach beyond this limit to their death.

Subahibi’s use of phrases such as “the limit of the world” carries a specific meaning in reference to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s early philosophical work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (TLP). We can identify declaration 5.6 of the TLP—as well as the relevant sub-declarations that follow from it—as particularly relevant to this point. These read:1

(5.6) The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

(5.61) Logic fills the world: the limits of the world are also its limits. We cannot therefore say in logic: This and this there is in the world, that there is not. For that would apparently presuppose that we exclude certain possibilities, and this cannot be the case since otherwise logic must get outside the limits of the world: that is, if it could consider these limits from the other side also. What we cannot think, that we cannot think: we cannot therefore say what we cannot think.

(5.62) This remark provides a key to the question, to what extent solipsism is a truth. In fact what solipsism means, is quite correct, only it cannot be said, but it shows itself. That the world is my world, shows itself in the fact that the limits of the language (the language which only I understand) mean the limits of my world. (5.621) The world and life are one.

(5.63) I am my world. (The microcosm.) (5.631) The thinking, presenting subject; there is no such thing. If I wrote a book "The world as I found it", I should also have therein to report on my body and say which members obey my will and which do not, etc. This then would be a method of isolating the subject or rather of showing that in an important sense there is no subject: that is to say, of it alone in this book mention could not be made. (5.632) The subject does not belong to the world but it is a limit of the world. [...]

(5.64) Here we see that solipsism strictly carried out coincides with pure realism. The I in solipsism shrinks to an extensionless point and there remains the reality co-ordinated with it. (5.641) There is therefore really a sense in philosophy that we can talk of a non-psychological I. The I occurs in philosophy through the fact that the "world is my world". The philosophical I is not the man, not the human body or the human soul of which psychology treats, but the metaphysical subject, the limit—not a part of the world.

This excerpt is liable to certain misinterpretations if it is read absent the logical atomism that is developed in the preceding declarations of the TLP. Similar problems will also occur if one excludes the enclosing declaration 5 (“propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions”) from their analysis. But whether we call Subahibi’s reading of the early Wittgenstein “wrong” or merely “creative,” we must first approach the game’s worldview in light of its own choice of such a reading.

As we have discussed, Subahibi’s first four chapters are a reimagining of Tsui no Sora. Insomuch as Tsui no Sora is a direct and fairly pessimistic depiction of the apocalypticism of the late 1990s, Subahibi revisits and rearticulates this object in order to turn the question around and examine the problem of subjectivity. We can think of the existential, abstract motifs that appear in the later half of Subahibi as an additional layer that rests atop the foundation of Tsui no Sora and its thematic legacy of socio-political atomisation in the post-Aum age. When Ayana paraphrases Wittgenstein at Yuki and says, “your limit is the limit of the world. Therefore, I am unable to tell or show you anything which you are not capable of seeing or speaking of,” we need to develop the tools to read this claim in consideration of Subahibi’s layered politico-existential structure.

Yuki herself is a useful example of this process at work. In Tsui no Sora, Yukito is unable to comprehend the conditions of his historical moment. As a result, he becomes blinded by and lost within an endless everyday existence. But since Yuki is instead immanently tied to the body of Tomosane Mamiya, she is “literally” present in the circumstances that Yukito was blind to. Her distance from Tomosane and Takuji is a purely "philosophical" rather than “psychological” phenomenon, in Wittgenstein’s sense. That is, in the sense that the subjective self is “not the [wo]man, not the human body or the human soul of which psychology treats, but the metaphysical subject, the limit—not a part of the world.”

Ayana expands on a related point when she says the following to Yuki:

Minakami, you too are trying to unearth something which you’ve hidden. […] The Wonderful Everyday. […] People live within the eternity of life. […] Life is a closed box. After all, death opens its doors for no-one. If you manage to conceal it, you will know nothing. Just like that, the Wonderful Everyday will be constructed upon the silence whereupon you cannot speak. […] Do you want to go outside? […] To the next world.

(Yuki rejects this provocation and says that Ayana is “starting to sound like Takuji Mamiya.”)

It is difficult to follow Ayana’s argument as given. For this reason, it would be productive to also consider Zakuro’s good end and its encounter with the various identities of Tomosane Mamiya. Because the Zakuro good end quite naturally focuses on Zakuro and Kimika as its primary characters, it is easy to overlook the fact that it is also a kind of hyperbolic good end for Yuki, where she manages to achieve an ongoing endless everyday existence without the suffering and difficulties of the other “routes.” However, Yuki’s precise circumstances throw some doubt upon the actual desirability of this result. Tomosane Mamiya operates through a system of three “souls” in one body (Takuji Mamiya, Tomosane Yūki, and Yuki Minakami). According to Tomosane Yūki’s interpretation, Takuji, who is the current head of the identity system, unconsciously wishes to be taken over by Yuki as his idealised personality (well, that certainly has gender implications). Tomosane’s role is to “defeat” Takuji and install Yuki as the new chief identity. Zakuro’s good end is the only outcome shown in the game where this concept plays out as originally envisioned, with Yuki being reborn as the sole personality occupying the body of Tomosane Mamiya at its conclusion. However, this result also sees Yuki lose her connection to the “objective” world observed by others; she enters an unreal endless everyday existence alongside the Wakatsuki twins, unable to reach Hasaki or any of the other unresolved threads of Tomosane’s past.

If we return to the Wittgensteinian vocabulary that appeared in Ayana’s earlier argument, that will render the problem a little differently. In this framework, Yuki cannot rely on any notion of an objective outside. There is no way for her to speak of any provable “other” beyond her enclosure within an endless everyday existence. Yuki is her own world; she does not belong to the world, but is a limit of the world. The alleged outside is not even an articulable type of absence, since, as in declaration 5.61, “what we cannot think, that we cannot think: we cannot therefore say what we cannot think”—and, in declaration 7, “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” The outside is not “anything” except the silence of non-knowledge. The Wittgensteinian notion of solipsism is not so much an affirmative claim that the outside, which is beyond the limit of the subject, specifically lacks existence. Rather, it is a sceptical claim that the subject is the limit of the world, and that there is therefore no sensible criteria for articulating the silence beyond this limit.

In this sense, a condition or situation that moulds the silence of non-knowing comes to implicitly be capable of changing the apparent shape of the world. On this point, we can return to Ayana’s argument that Yuki’s endless everyday existence is “constructed upon the silence whereupon you cannot speak.” When Yuki loses her experiential connection to Takuji, Tomosane, and Hasaki, it is not as though she has any criteria by which to speak of this shift as a moment of alienation or removal from the “objective” world. From Yuki’s perspective, the world—her world, of which she is the limit—has changed in its concrete and verifiable content. As Tomosane also argues:

There is no exterior or anything. It’s all just the world. It’s all just my world. […] I don’t really feel like I’m alone in the world. You’re right in front of my eyes, so you definitely exist. I would even go so far as to say that Yuki Minakami and the Wakatsuki sisters existed as well, even if they didn’t exist to you. But still, even then, my world ends at the limit of my world. I don’t know anything beyond the limit of my own world. I have no way of knowing anything else. That’s why I’m only me. It’s a bit strange for me to say this after sharing my body with multiple people. No, especially because of that, I can say that I’m no one except myself.

Nobukatsu Kimura amends this description, observing that “even if we had an exterior, it would just be another part of the world we know.” That is, transcendence is impossible because stepping beyond the limits of yourself is simply an act of including the previous outside within a new inside. Looking at the universe places that universe within one’s brain. Yuki’s predicament is something like the inverse of this phenomenon: retreating from knowledge of something that was once known—to hide something, in Ayana’s terms—shoots that something out into the silent non-existence of the inarticulable outside. As a sociological matter, Ayana identifies the endless everyday of contemporary society as just such an expatriation. Contemporary life exiles death and builds up a new life-world atop the silence left in death’s place. Yuki enacts a similar principle in microcosm by living within a world where Takuji, Tomosane, and Hasaki are absent. The Wakatsuki twins, for example, exist precisely atop the silence left by Hasaki’s absence.

Our analysis thus far has disorientingly jumped back and forth across multiple thought trains. The necessity of this manoeuvre lies in the fact that Subahibi itself develops along a series of parallel conceptual tracks. However, a number of these disparate strands are ultimately brought together through the problem of Tomosane Mamiya’s body. Or more exactly, Tomosane is the instrument that Subahibi uses to trace the points of contact between its various thematic paths. Across the Yuki, Takuji, and Tomosane chapters, we see various worlds. These worlds are each, in the sense discussed above, “constructed upon the silence whereupon you [the individual narrators] cannot speak.” The shared embodiment of these individuals demonstrates that these separate worlds are not rooted in a merely physical or psychological sense of subjective difference. Moreover, it is not that different subjects are different parts of the same world. The point is to present a situation that overlaps exactly with Wittgenstein’s notion of the subject as the world—of the world as the terrain constituted by the subject’s limit. Since the identities that constitute Tomosane share the same bodily limit whilst forming entirely different worldly limits, this demonstrates that the limit of the self-world is not reducible to an empirical phenomenon of physical embodiment. Each person can only treat the world as their world, nothing more and nothing less.

The first and central problem is whether accepting the givenness of this subjective self-world automatically entails solipsism. Wittgenstein answers in the affirmative throughout declaration 5.6. However, his acceptance also begs the question of what solipsism means to him, since he also identifies it with “pure realism.” That is, we must ask: even if the world is constituted of one person and one person only—the philosophical subject—does that demote all others to comparative non-existence? At the least, must the solipsist doubt the worlds of others even if they provisionally accept the existent there-ness of others? (“You’re right in front of my eyes, so you definitely exist,” as Tomosane accepts.) One notable excerpt from the conclusion of chapter two offers a hint as to Subahibi’s stance:

The difference between me and the world. […] They’re the same. […] if you stood at the edge of the world, you would probably see the shape of the world just like I do. So you would be the same as the world too. But that really doesn’t make sense. If the world is me, why can’t I see the world that you see? Even though you are in my world, I can’t see the world you see. I’ve never seen the world that you do. They’re like parallel universes that can never cross. […] I can’t see the world you live in. […] But… Is that really the case? […] If every person has been equally allotted one singular world… […] There must be a way for the worlds to become one.

That is, even while accepting solipsism as its ground, there is a degree of openness to the shared ground of the world. This is another point which Subahibi roots in the unique mode of existence that is taken up by Tomosane. While it is true that each individual who shares Tomosane’s body constitutes a separate and irreconcilable self-world, they each depend on their mutual separateness as foundational to their own identities. Put another way, Tomosane’s identity as himself depends on the recognition that the person who appears as Yuki is a demonstrably existent person who can nonetheless be defined negatively as not-Tomosane within the same body. Tomosane accepts himself as his world. Yuki overlaps with himself at such a level that Tomosane cannot doubt her existence. However, she separately constitutes her own world in a silence whereof he cannot speak. The result, as Tomosane puts it, is that “especially because” he is “sharing my body with multiple people,” he is able to “say that I’m no one except myself.” Subahibi builds a ground for solipsism that is curiously accepting of the existence of others.

One effect of this whole stance is that the second half of the story is able to redefine the same division between inside and outside which is so decisive in Tsui no Sora, as well as in the earlier chapters that recapitulate some of the same thematic terrain as that earlier game. Subahibi’s ultimate model of subjectivism rejects the concept of transcendence and the outside in general. Everything is one contiguous inside in the sense of being coordinated with the self-world. The socio-political context that drives the desire for transcendence, however, remains all the same. The post-Aum age is still representative of an historical epoch where people feel highly insulated by their technologically mediated forms of existence. The impossibility of transcendence does not mean that the ontologically isolating endless everyday existence is any less of a defining crisis for the youth that are trapped in the nihilistic Lost Decades of economic stagnation and apocalypticism. Instead, the extreme phenomena of Tsui no Sora are revealed to be equally impotent as solutions to that condition. Without an outside to transcend to, people can only aspire to one thing: living happily.

Third division: Down the rabbit hole

If we follow Subahibi in taking the multiple personalities of Tomosane Mamiya as a useful analogy from which to think through the problem of subjectivity, there is one supreme unanswered question that remains: If different worlds—different subjects—can be equivalently constituted seamlessly both within and without the boundary of a single body, is there any meaning to the division between bodies in the first place? Is there any fundamental difference between sharing a physical space with others and sharing a body with them? Dealing with the question from a different angle, there is a problem of doubt baked into Subahibi’s attempt at inclusive solipsism. If we let the whole world, including others, into the horizons of the brain, the fact of their apparently exterior existence does not change the metaphysical conclusion that they are included wholesale within the limit of one’s world. Even if we have chosen to accept their existence, we cannot prove their otherness. As Ayana claims, “if a single soul viewed every perspective, that would be enough” to constitute the universe of self-worlds. It is possible that “the entire world is made up of ‘me’. That’s why I can understand you.”

In the epilogue chapter, Tsui no Sora II, Ayana leads Yuki through a thought experiment that drives towards a similar conclusion. Her argument in this case is positive and rooted in the peculiarities of the events featured throughout the story, as opposed to the negative form of the argument laid out above. The Yuki who appears in Tsui no Sora II remembers the events of both versions of Down the Rabbit Hole—and seems to show a vague awareness of the events as told by the other four narrators of Subahibi as well. Ayana probes Yuki, enquiring as to how this can be the case within the bounds of a purely individuated definition of subjectivity. As a simple example, the phrase “End Sky” originally appears in the first chapter of the story. However, if we wish to interpret this chapter as a simple dream sequence, it becomes difficult to explain the presence of this phrase throughout the rest of the story. A superficially plausible guess is offered that Takuji was unconsciously sharing Yuki’s memories. But this explanation becomes less useful if we closely inspect Down the Rabbit Hole I, especially in light of the numerous references to Zakuro’s life in a sense beyond what Yuki or Takuji ever knew.

No final conclusion or absolute answer is given in the course of this epilogue. It simply offers what Ayana calls “annotations” to the questions raised by the rest of the game. One such annotation is Ayana’s suggested theory behind the peculiarities of Down the Rabbit Hole I, which she identifies as the “eternal transmigration of the soul.” If we do not let the category of the physical body constrain our thinking, we might choose to consider the possibility that all five narrators of the story share a fundamental essence comparable in certain respects to the problem of Tomosane Mamiya. The account that Ayana gives is of a single soul that reincarnates in order to experience each perspective and each story within the horizon of one individual self. This would allow for a kind of surface-level explanation for the whole story, but its basis is thin enough that many players may discard it as little more than an unserious thought experiment. That said, even if we do not take it too literally, the theory has quite a bit more weight behind it than a mere thought experiment if read in a fuller context.

The format and content of Subahibi’s epilogue mirrors elements in Tsui no Sora’s own epilogue chapter, titled And Thereafter. Riffing on that game’s exploration of nihilism through Nietzsche and the other early existentialists, And Thereafter features a pair of discussions between Yukito and Ayana centred on Nietzsche’s thought experiment of an “eternal recurrence.” Nietzsche invites us to imagine the possibility that our lives are not temporary blips in the sempiternal flow of linear time, but that the human soul repeatedly and endlessly lives out the experience of its mortal life. That is, to imagine a form of reincarnation based around living the same life forever with no variability. Nietzsche’s challenge is one of existential nihilism and meaning: Do we live our lives in such a way that we could tolerate being trapped in them for eternity, without the escape of death? And is a life that is lived in accordance with this imaginary eternity superior to the life that treats itself as limited and perishable?

Tsui no Sora’s responsiveness to the socio-political phenomenon of Miyadai’s endless everyday existence is rooted in its fascination with this Nietzschean thought experiment. The endless everyday existence of contemporary Japanese capitalism would be utterly intolerable under the conditions of an eternal recurrence. Ayana provokes Takuji on this point, asking him to imagine “a wonderful high school life. A wonderful girlfriend. Wonderful friends. A wonderful life. And it goes on for hundreds of years. And it goes on for thousands of years. And it goes on for tens of thousands of years. And it goes on for hundreds of thousands of years. And it goes on for millions of years. And it goes on for tens of millions of years. And it goes on for hundreds of millions of years. And it goes on for billions of years. And it goes on for tens of billions of years. And it goes on for trillions of years. And it goes on for quadrillions of years. And it goes on for tens of quadrillions of years. And it goes on for hundreds of quadrillions of years. And it goes on for thousands of quadrillions of years. And it just keeps going. […] A wonderful girlfriend. Wonderful friends. A wonderful life. Forever and ever.” Upon hearing of this encounter later during the epilogue, Yukito remarks simply, “that’d basically be Hell.” In other words, an actually endless everyday existence in the comfort of Japanese capitalism would be, contrary to Miyadai’s hopes, unimaginably horrific. However, in the course of both Tsui no Sora and especially Subahibi, we see that the alternative of death as the moment of transcendence and escape from an endless everyday existence is similarly empty. In the Japan of the post-Aum age, there is no “good” life, whether lived for the everyday or the transcendent, under conditions of an eternal recurrence.

The 2020 Remake of Tsui no Sora reimagines And Thereafter as a new epilogue titled Numinöse. It retains the same pair of discussions centred on the motif of an eternal recurrence. However, in the “true end” second variant of Numinöse, Ayana adds a Spinozaist reading of the concept of eternity to the problem of reincarnation and recurrence. Spinoza is a pantheist who argues that the ideas and material of apparent reality are all reducible to the singular eternal substance of God. As Yukito summarises his own understanding, “if we assume that infinity means to encompass everything, and that humans are just a single part of a chain on this infinite plane, then perhaps humans are both ‘one’ and ‘all’. It feels like there is also the reasoning of the universe within the reasoning of humans.” Spinoza’s point of departure from other pantheistic strands, such as Neoplatonic Christian theology, comes in his far more fastidious commitment to the ultimate unity of all of existence. For a Neoplatonist, humanity is a fallen emanation of the eternal Lógos of God, and its capacity for understanding is circumscribed by its lower place within the great chain of being. But for Spinoza, the limitations of human understanding are simply a matter of perspective within the ultimate unity of all substance, and even the divine sense of eternity—the sub specie aeternitatis—is accessible in principle to human comprehension.

With only the slightest vulgarisation, we can reformulate Spinoza in a way that brings his essential relevance to light: for Spinoza, the only reason that people think of themselves as different is because they occupy different standpoints. But the truth from the sub specie aeternitatis is that everyone is of one ultimate essence made up by God’s unified standpoint. In a Wittgensteinian vocabulary, the metaphysical subject is the world. The fact, then, that everyone shares the same world implies that they share the same metaphysical subject. “The Sky. It’s the sky… I can see the sky. Why… Why is the sky blue? Probably… Because it’s connected to every other sky that exists… But… this sky… and the End Sky… aren’t connected. Because after all, how can it be connected to it, when it’s the thing itself? If this sky is connected to the End Sky… then without a doubt, this is the End Sky.”

Ayana’s theory of the eternal transmigration of the soul brings these various philosophical strands together into a singular explanation. She proposes that Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence is true in the sense that one soul is an eternal witness to its life. But that life encompasses everything and everyone. The singular soul endlessly recycles itself to experience and thereby constitute all worlds from all standpoints. This one soul is the metaphysical self in Wittgenstein’s terms. It therefore remains true to say that there is no outside and no transcendence beyond the world that is everything, but people further circumscribe themselves by hiding the reality of this everything, and thereby live in an everyday “constructed upon the silence whereupon you cannot speak.”

Part Two – The Purification of the Idea

We tend to think of the defining events of an epoch as being, almost by definition, unprecedented or novel in some way. However, part of the special resonance that the Aum incident carried in the Japanese imagination was rooted specifically in its lack of historical originality. A generation prior, Japanese political life also came to be defined by a sudden encounter with nihilistic terrorism. During the Winter of 1971/1972, a small left-wing sect of political extremists known as the United Red Army (URA) stepped out from their relative obscurity onto just shy of 90% of Japanese TV screens.2 However, unlike the Aum incident, the chief victim of the URA was not the wider public, but the group itself. In the manner of a doomsday cult, the group suddenly started massacring its own members and then disintegrated as an organisation.

This URA incident quickly “gained iconic status as an event that announced the end of the postwar New Left movements that had pursued revolutionary dreams in Japan.”3 The significance of the moment was equal parts cerebral and visceral—abstract and immediate. Its sheer violence produced a spectacle that captured the attention of the nation, and the subsequent flurry of analysis and criticism resulted in an effective cultural embargo of the far left of Japanese politics which lasted for decades.

The aftermath of the Aum incident in the late 1990s was naturally dominated by comparisons to this earlier URA incident. For their part, many of the important cultural theorists of the immediate post-Aum era, like Shinji Miyadai and Masachi Osawa, emphasised the differences between the incidents much more than their similarities. And we must similarly keep these differences in mind: the Aum attacks were carried out by an apocalyptic religious movement, whereas the URA was a serious and secular political organisation. However, we can nonetheless use the URA incident as a significant lens through which to consider the phenomena of terrorism and extremism. In time, these insights will prove highly relevant to our broader topic.

The facts of the United Red Army incident

Even prior to the incident itself, the URA was a peculiar fixture in the constellation of militant organisations on the Japanese far left that rose up in the late 1960s:

The United Red Army was the product of a rare merger of two radical organizations—the Red Army faction of the second Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei (Communist League) and the Kakumei Saha (Revolutionary Left)—that shared the desire to destroy the existing political system in favor of a communist regime in Japan through militant confrontations with the state authority.

Yoshikuni Igarashi, Dead Bodies and Living Guns

More exactly, to note the relevant internecine distinctions, the Red Army Faction was a Trotskyist-Maoist Third Worldist organisation dedicated to the violent overthrow of the Japanese government—an act through which it hoped to catalyse a “world revolutionary war” in accordance with a doctrine of permanent revolution. Meanwhile, the Revolutionary Left “embraced anti-American patriotism, while aspiring to a revolution on the national level under Maoist ideology.” This is to say that despite certain ideological tensions, which proved proportionately important in the fullness of time, the two organisations also had sufficient ideological overlap to justify a contingent unification. They merged the administration of their terrorist operations under the label of the URA.

Concerning the URA incident itself, its characteristic brutality was at least partially anticipated by prior violence that was carried out by these two constituent groups. In late 1971, just prior to the incident itself, the Revolutionary Left executed two of their own members in order to prevent their defection to the police. But even before this, in 1970 the group had made a name for itself with an attack on a lightly staffed neighbourhood police station in Tokyo, which was intended to kill or injure any police officers present and to steal their guns. (The attack was a failure, resulting in the death of one of the Revolutionary Left militants.) Around the same time, the Red Army Faction attacked police boxes using Molotov cocktails and improvised explosives across Kansai in 1969 and 1970, hoping to set off a revolutionary action that they referred to as the “Osaka War.” They were also behind a series of kidnappings and beatings of more moderate members of the Communist League during their schismatic break with the group in 1969.

In fact, it was precisely this string of clearly violent, but nonetheless highly ineffective, outbursts by both groups that brought about the immediate circumstances of the URA incident. By 1971, both groups were being aggressively pursued by the police. But they had also failed to accumulate the personnel or weapons to effectively fight back in their imagined revolutionary war. Therefore, a plan was concocted to pool their weapons, explosives, finances, and members in mountain hideouts across the Winter of 1971/1972, and to train for their planned revolutionary war against the Japanese police:

The two organizations found themselves in need of each other. The Revolutionary Left had weapons with hardly any cash, while the Red Army faction managed to raise funds by robbing a number of financial institutions during the months the six members of the Revolutionary Left hibernated in Sapporo. The Red Army faction also gained know-how in producing homemade explosive devices. Yet, despite repeated attempts, it had never succeeded in obtaining firearms by force. The guns that the Revolutionary Left owned but were unable to use would complete the Red Army Faction’s preparation for armed uprisings.

Yoshikuni Igarashi, Dead Bodies and Living Guns

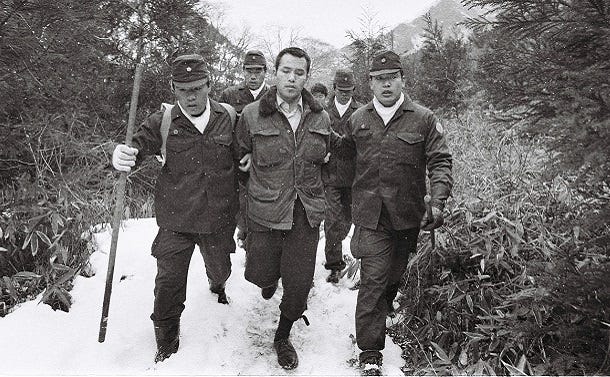

However, this joint training session also failed; the following disintegration of the URA over the course of the Winter of early 1972—first through a series of self-inflicted purges within their own mountain hideouts, and then during a climactic hostage standoff with police at a ski lodge on Mount Asama—came to be known as the URA incident.

The overall incident can be separated into two sub-incidents: Firstly, there were the lynching incidents in the URA’s hideouts. Secondly, there was the siege on Mount Asama. Although it was the sensational and public nature of the latter that originally captured the attention of the media, commentators soon turned to scrutinising the preceding purges. “In the few weeks between December 1971 and February 1972, ten of the original 29 participants in the United Red Army’s military training camp were killed in the name of sōkatsu (self-critique), while two were executed for the alleged crime of contemplating escape.” Altogether, that makes for twelve executions in a little over a month. And for a survival rate of less than 60%. As the sheer barbarism of the events became clear, they conjured the worst excesses of the Stalinist Great Purges or the then still-ongoing Maoist Cultural Revolution. “As soon as these acts were reported by the media, whatever sympathy the public had afforded the group immediately dried up. Even those who had defended the United Red Army’s armed confrontation with the police dared not support its members’ bloody purges.”

The example of Mieko Tōyama is particularly evocative. Tōyama retained a position of relative authority within the URA through her marriage to Takahara Hiroyuki—an Executive in the Politburo of the Red Army Faction. However, her standing steadily declined during the joint training session of 1971/1972—especially once she was antagonised by the leader of the Revolutionary Left, Hiroko Nagata. “In early December 1971, Nagata Hiroko insistently criticized Tōyama for keeping long hair, wearing make-up, and refusing to dispose of her ring.” A month later, after such trivialities compounded beyond all reason:

[Tōyama] was ordered by Mori to beat herself on 3 January 1972. Surrounded by the other members, Tōyama repeatedly hit her face with her own fists for about 30 minutes until it was a swollen bloody mess. […] Tōyama dutifully applied the ideological assistance to herself. Yet her self-assistance was deemed insufficient for completing her comprehensive self-critique; and the others rendered helping hands in her deadly endeavor, hitting her, cutting her hair, and finally leaving her tied up until her death on 7 January.

Yoshikuni Igarashi, Dead Bodies and Living Guns

Tōyama’s case was, however, just the most sensational among a sequence of undeniably horrific incidents.

In parallel to the accelerating violence of the URA, their strategic position collapsed. Among those who were unwilling to remain in a situation where indiscriminate murder was a tangible possibility, the obvious alternative was to flee from the mountain—and perhaps, to defect to the police and share information about the rest of the group. This is naturally exactly what happened, which pushed the surviving loyalists of the URA into a figurative corner.

On 16 February 1972, after realizing the police were encroaching on them, the remaining members abandoned their mountain cave in Gunma Prefecture, to which they had moved to evade police pursuit a few days earlier. In order to outwit the police search teams, members decided to take a treacherous winter mountain route to reach the Nagano Prefecture part of the Japan Alps.

Yoshikuni Igarashi, Dead Bodies and Living Guns

The majority of the members were arrested en route, but the last five members, fearing arrest, took a hostage and locked themselves in a nearby ski lodge. A resultant nine-day police siege captured the attention of the nation and inculcated a climate of retroactive interest in the lynching murders once their grotesque results were uncovered.

Isolation and cultishness

The URA may have been fastidiously secular. But it nonetheless borrowed a great deal from the organisational principles of cults and other apocalyptic movements. According to Thomas Robbins and Dick Anthony:

The decline of traditional mediating structures raises the prospect of pervasive atomization and widespread "homelessness" or loss of social rootedness (Berger and Neuhaus, 1977). In fact, however, there is some tendency for declining mediating collectivities to be replaced by emergent "social inventions" (Coleman, 1970) and encounter groups, cults and communes, which operate to detach young persons from exclusive reliance upon the nuclear family for interpersonal relationships and value transmission. Such groups create settings for "extended communal relations transcending kinship ties" and thus constitute "contemporary attempts to create new intermediate relations between individuals and primary groups on the one hand, and traditional … secondary groups on the other, through extended primary relations" (Marx and Ellison, 1975:455). […]

The current proliferation of esoteric movements as well as the evangelical resurgence can be viewed as part of a broader "sectarian reaction to mass society," which is providing an impetus for the emergence of a variety of movements. These groups qua mediating structures have been depicted as performing a variety of adaptive and therapeutic functions for individual devotees (Snelling and Whitely, 1973; Petersen and Mauss, 1973; Marx and Seldin, 1973; Gordon, 1974; Zaretsky and Leone, 1974; Robbins et al., 1975; Bradfield, 1976; Anthony et al., 1977; Anthony, 1980; Galanter and Buckley, 1979). as well as integrative and tension management functions with respect to the social system (Robbins, et al., 1975; Robbins and Anthony, 1978).

Thomas Robbins & Dick Anthony, Cults, Culture, and Community

In a similar manner to those cults that “create settings for ‘extended communal relations transcending kinship ties’,” the URA forced its members into a condition of extreme sociological and geographical isolation via its system of mountain bases. The URA was also closely tethered to a small caste of charismatic ideological leaders—especially Tsuneo Mori and Hiroko Nagata, whose wills came to be identified with the will of the group itself. The isolation of the URA partisans from mass society may have been a natural extension of their guerrilla tactics, but it also had striking impacts on their organisational principles and the psychological posture of its members.

Mori, for example, repeatedly demanded that the members of the group “communise” themselves. This “communisation” of the self was posited as the only method of freeing a would-be revolutionary from their naturally counterrevolutionary disposition. But neither Mori nor his targets demonstrated any clear understanding of what this concept meant in practice. The accusations which motivated the purges of the URA incident—such as failing to prepare enough water bottles or being excessively attached to personal beauty—were so directionless, vague, and broad that communisation came to be defined as a tautological buzzword. Communisation was simply equivalent to doing the ‘right’ thing in whatever revolutionary terms Mori happened to accept in that moment.

Yet, the relative incoherence of the URA incident, as a question of the content of the victims’ behaviour, is far less mysterious when studied in terms of the “standpoint” of the members of the group as revolutionary subjects. According to Akihiro Kitada, “Marxist ideological spaces bring attention to the narrator’s position, intensifying interest in self-consciousness and self-negation as methodological issues of identity formation.”4 In analysing the importance of this fixation, Kitada quotes Michinori Katō, a survivor of the URA incident, who in turn explains that “making a mistake did not stop at admitting fault and declaring ‘I will carry out self-critique’. It also involved digging down and unearthing the original ideological causes of the mistake. Self-critique was a presentation of one’s personal history as the fundamental cause of the mistake, and then an analysis of how one would transcend it.”5 Communisation is consequently defined by Kitada as:

[The effort] by which an individual subject obtains the physicality of a revolutionary warrior via “comradely discussion, mutual debate, and self-critique.” […] Mori’s favoured catchphrase was “from the perspective of communisation;” saying things such as […] “from the perspective of communisation, it is not acceptable to become the centre of attention.” […] It is almost impossible to locate any conceptual core to this “perspective of communisation.” […] However, this does not mean that the ideology of communisation was haphazard or meaningless. It was a meta-ideology of negation that could not be articulated in positive terms. […] The theory of communisation was a network of discourses that sustained a desire for the impossible state of total communisation; this state did not need to correspond to any exact goal or end. […] It is best to think of the privileged position they [Mori and Nagata] held in this discursive space. […] A deified, transcendent authority is necessary to see through the self-deception of self-negation; Mori and Nagata instrumentally took on the role of that authority.

Akihiro Kitada, Laughing Japanese Nationalism

In other words, the operation of communisation in the URA incident was not a matter of behavioural content, but of position. What defined counterrevolutionary conduct—even demonstrably harmless conduct—was that it could not be articulated “from the perspective of communisation,” which was itself instrumentally attached to Mori and Nagata as a function of their hierarchical leadership. This coincidence between leadership and the group’s alleged collective desires may have been rooted in a distorted reading of secular Marxist theory, but one of its practical consequences was an analogy to the organisational principles of doomsday cults and religious extremists.

The “idea” as phenomenon

It is one thing to empirically demonstrate that cults and extremist organisations use isolation as an instrument to—whether intentionally or coincidentally—condition their members for the kinds of violence that we see in the Aum and URA cases, as well as in related fictional depictions such as Tsui no Sora and Subahibi. But this factual finding is insufficient to fully grasp the phenomenon. We also need to develop a philosophical and conceptual account of the inner mechanisms that lie beneath the organisational principles of isolation.

An obvious place to turn is Shinji Miyadai’s description of ontological isolation in contemporary technologised capitalism. Miyadai’s account of the Aum incident rests on the same “decline of traditional mediating structures” and “pervasive atomization and widespread ‘homelessness’ or loss of social rootedness” that is identified by a cause of cultish organisations by Robbins and Anthony. However, Miyadai’s diagnosis refers to a generalised, society-wide condition of social dislocation and ontological isolation. This makes it a slightly different phenomenon from the narrowly tailored isolation that is practised by cults and extremist organisations. As Robbins and Anthony highlight, this cultish isolation is carried out as a response to the wider circumstances of contemporary social atomisation. But Miyadai’s theory does not speak to a cult’s own resultant internal dynamics.

Under Miyadai’s framework, technological atomisation disrupts and fragments the mediating institutions of society. However, we should firstly question why it is that cultish attempts to reconstitute a new community in the place of these institutions lead to a totalising hierarchical structure in the mould of Mori’s theory of communisation. A second question further concerns the reason that this circumstance further carries the potential to erupt into apocalyptic violence. Together, answering these will clarify the fundamental basis behind the Aum and URA incidents. Moreover, doing so will allow us to return to Subahibi with a new analytical lens.

One of the more readily applicable attempts to answer these questions came about directly in response to the URA incident. Kiyoshi Kasai, a former Marxist of the same “[nineteen] sixty-eighter” generation as the participants in the URA incident, made a considerable splash in the landscape of Japanese political thought with the publication of his seminal 1984 work, The Phenomenology of Terrorism: An Introduction to the Critique of Ideas. In The Phenomenology of Terrorism, Kasai attempts to break with the kinds of sectarian and ideological Marxism that he sees as being embodied by the URA incident. He further tries to rescue the revolutionary potential of spontaneous moments of anarchic action—such as the Paris Commune, Russian Soviets, or even the counter-cultural youth rebellion of May 1968—as standing apart from the totalising obligations of Marxism and dialectical materialism. For our purposes, the book is highly illustrative in its detailed attempt to get behind the nature of ideological violence and cultish thinking.

Kasai begins this task with a phenomenological account of ideological thinking as a conditioned state of existence. Kasai structures his vision of the “idea” (kannen) into four basic forms:

● The Self-idea (jiko kannen)

● The Communal-idea (kyōdō kannen)

● The Partisan-idea (tōha kannen)

● The Ensemble-idea (shūgō kannen)

There is a danger of mistaking the meaning of these terms when they are taken as strictly sociological or political categories. Firstly, it should be noted that Kasai’s phenomenology centres human experience, and not abstract things. We can analogise this to another recurring motif for Kasai: the forms and modes of pain as a sensation that is both physically embodied in a spatial dimension and yet deeply personal and interior. Relatedly, attempting to interpret the Self-idea as uniquely subjective, as next to the objective-seeming forms of ideas that correspond to the terminology of the collective group, would be to make a decisive analytical error. All of these forms of the idea are phenomena that humans occupy in the first-person.

However, it would also be a mistake to confuse Kasai’s ‘idea’ with the mental activity of thinking. Kasai’s idea is not equivalent to the process of interiority or the experience of being within a mental process. It is instead concerned with the existence of concepts, understandings, or frameworks as phenomenal appearing-beings in their own sense. “Ideas are thought-things, mental artifacts.”6 In the same typology as pain, the idea dwells within a person, but in some sense comes from somewhere else—somewhere tangibly real and at some distance from the imaginary and thinking processes. This is, in other words, the first-person encounter with comprehensible abstractions as-such.

For Kasai, all ideas are produced through alienation. “The basic character of the idea is ‘self-deception’.”7 This is because alienation and abstraction are, structurally speaking, nearly identical. Any attempt to comprehend the world and retain it will be under constant assault from the reality of the world; not merely because of some empirical contradiction between the two—it is rather that the attempt to hold the world in comprehension, and to enclose or encapsulate it, is threatened by the non-ideational structure of the material real world. Hence, ideas in general correspond to “the ideational restoration of a lost real world.”8